Who Is Being Served?

There is no single data source about the recipients of evidence-based early childhood home visiting services. The NHVRC reached out to home visiting models considered evidence based in 2018 and to state, territory, and tribal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) awardees.

Their responses—including a 100 percent response rate from models—move us closer to depicting the hundreds of thousands of families working with evidence-based home visiting programs to pursue better lives.

All 15 evidence-based models operating across the United States in 2018 provided data on the number of families and/or children served. Nine models also provided data on the characteristics of those participants. According to the data the evidence-based models provided—

Learn More About the National Landscape

Photo courtesy of Lisa Martin

What Do We Know About Other Home Visiting Models?

The Home Visiting Yearbook primarily shares data on home visiting provided by models designated as evidence based by the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) project. Last year, we began exploring information about emerging home visiting models that demonstrate some evidence of effectiveness but have not been designated by HomVEE as evidence based.

Many emerging models are well established, and several meet some criteria of rigorous evidence. All play an important role in the home visiting landscape, often serving many families or being implemented across several locations.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to designating models as evidence based. Entities such as HomVEE, the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, and state-level organizations use different—although sometimes overlapping—criteria to review a program’s effectiveness. For example, HomVEE looks at the type of study used to evaluate a model and study characteristics such as attrition and confounding factors.

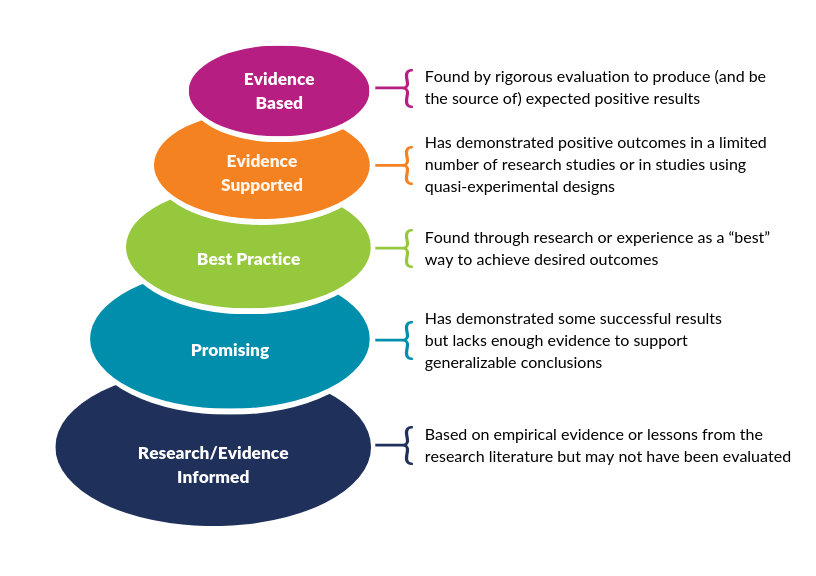

Evidence builds along a continuum. Although the process may seem linear, various steps or iterations are often involved in moving forward along the continuum. Some emerging models will reach the final phase of the continuum with time. Others may not advance for various reasons. For example, rigorous evaluation takes time and money, and programs may not have enough personnel to conduct an experimental study.

Continuum of Evidence for Home Visiting Models

Sources:

FRIENDS National Resource Center. (n.d.). Evidence-based practice in CBCAP. Retrieved from [https://friendsnrc.org/evaluation-toolkit](https://friendsnrc.org/evaluation-toolkit)

State of Michigan. (n.d.). Effective and promising practice interventions for increasing healthy eating, increasing physical activity and decreasing tobacco use and exposure in community-based settings. Retrieved from [https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/BHC_TA_Manual_2008-09_244485_7.pdf](https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/BHC_TA_Manual_2008-09_244485_7.pdf)

Child Care and Early Education Research Connections. (n.d.). Child care & early education glossary. Retrieved from [https://www. researchconnections.org/childcare/childcare-glossary](https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/childcare-glossary)

Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions: Evidence-based practices. Retrieved from [https://dbhids.org/epic/frequently-asked-questions#toggle-id-4](https://dbhids.org/epic/frequently-asked-questions#toggle-id-4)

Cooney, S. M., Huser, M., Small, S., & O’Connor, C. (2007). Evidence-based programs: An overview. What Works, Wisconsin Research to Practice Series 6. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin–Madison/Extension.