Before the NHVRC launched in 2017, there was no single data source about the recipients of evidence-based early childhood home visiting services. For this yearbook, the NHVRC reached out to home visiting models considered evidence based in 2022 and to state, territory, the District of Columbia, and Tribal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program grantees.

Their collective response moves us closer to depicting the hundreds of thousands of families working with evidence-based home visiting programs to pursue better lives. We recognize the information presented in the 2023 Home Visiting Yearbook likely undercounts the reach of home visiting services in 2022; still, we believe it presents the best nationwide look at home visiting services.

Seventeen evidence-based models operating across the United States in 2022 provided data on the number of families and/or children served.

According to the data received—

Of the more than 2.8 million home visits provided, at least—

Learn More About the National Landscape

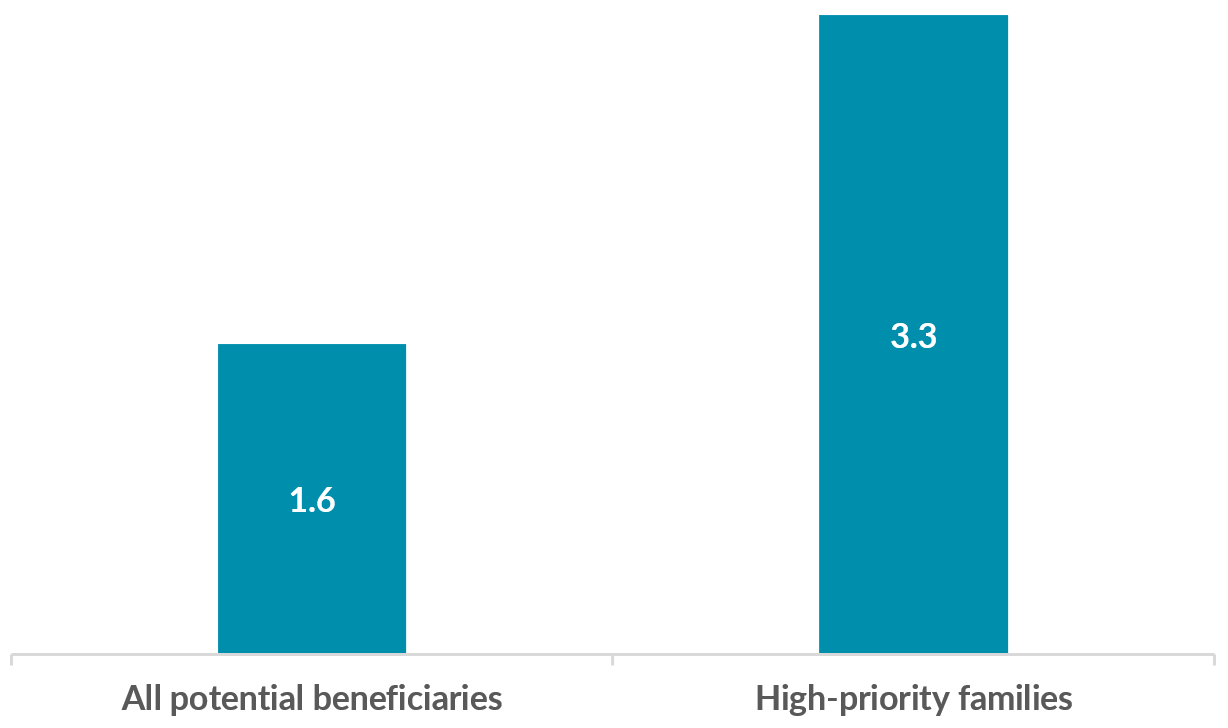

Although the number of families served by evidence-based models is substantial, it represents only 1.6 percent of the more than 17.3 million pregnant caregivers and parenting families who could benefit from home visiting. The percentage of families served rises to 3.3 percent if one restricts the pool of potential beneficiaries to our estimate of high-priority families. (Source: The 3.3 percent estimate makes the simplifying assumption that the 270,890 families served are high-priority families.)Go to footnote #>1

Percentage of Families Served (2022)

Source: Calculations based on data collected from 17 evidence-based models operating in the United States in 2022, and tabulations of the [American Community Survey](https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/) (2017–2021).

What Do We Know About Other Home Visiting Models?

The Home Visiting Yearbook primarily shares data on home visiting provided by models designated as evidence based by the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) project. Since 2018, we have explored information about emerging home visiting models that demonstrate some evidence of effectiveness but have not been designated by HomVEE as evidence based.

Many emerging models are well established, and several meet some criteria of rigorous evidence. All play an important role in the home visiting landscape, often serving many families or being implemented across several locations.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to designating models as evidence based. Entities such as HomVEE, the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, and state-level organizations use different—although sometimes overlapping—criteria to review a program’s effectiveness. For example, HomVEE looks at the type of study used to evaluate a model and study characteristics such as attrition and confounding factors.

Evidence builds along a continuum. Although the process may seem linear, various steps or iterations are often involved in moving forward along the continuum. Some emerging models will reach the final phase of the continuum with time. Others may not advance for various reasons. For example, rigorous evaluation takes time and money, and programs may not have enough personnel to conduct an experimental study.

Continuum of Evidence for Home Visiting Models

Sources:

FRIENDS National Resource Center. (n.d.). Evidence-based practice in CBCAP. [https://friendsnrc.org/evaluation-toolkit](https://friendsnrc.org/evaluation-toolkit)

Child Care and Early Education Research Connections. (n.d.). Child care & early education glossary. [https://www. researchconnections.org/childcare/childcare-glossary](https://www.researchconnections.org/childcare/childcare-glossary)

Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. (n.d.). Frequently asked questions: Evidence-based practices. [https://dbhids.org/epic/frequently-asked-questions#toggle-id-4](https://dbhids.org/epic/frequently-asked-questions#toggle-id-4)

Cooney, S. M., Huser, M., Small, S., & O’Connor, C. (2007). Evidence-based programs: An overview. What Works, Wisconsin Research to Practice Series 6. University of Wisconsin–Madison/Extension.

“After” the Pandemic: Realigning Home Visit Schedules to Meet Family Needs

In 2022, ParentChild+ saw a decrease in the number of home visits provided by sites using the model, although the number of families served remained stable compared to the prior year. The decline in visits doesn’t reflect a gap in services, says Chief Executive Officer Sarah Walzer, but rather a “rightsizing” of support to families as the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic began to ebb. She cites the unique circumstances of the early pandemic when families experienced near-universal roadblocks to accessing resources and began reaching out to home visitors more often through FaceTime and text. Even virtual visiting involved more interactions with families, as home visitors began dropping off books and toys related to upcoming sessions, providing another regular touchpoint.

Caregivers also turned to home visitors to pick up items like food and diapers when they could not leave their homes or ask a friend for help. Issues like family isolation, food insecurity, and limited transportation continue, Walzer says, but the pandemic uniquely magnified them—as well as home visitors’ constant and continued presence for families in difficult times: “If families hadn’t had that [home visitor] they trusted to call and share their struggle with, they often would not have had anyone else.”